Cart

6 min read

Medic Minute #2 – Cold Injuries

Medic Minute #2 – Cold Injuries

(Frostbite, frostnip, immersion foot, hypothermia)

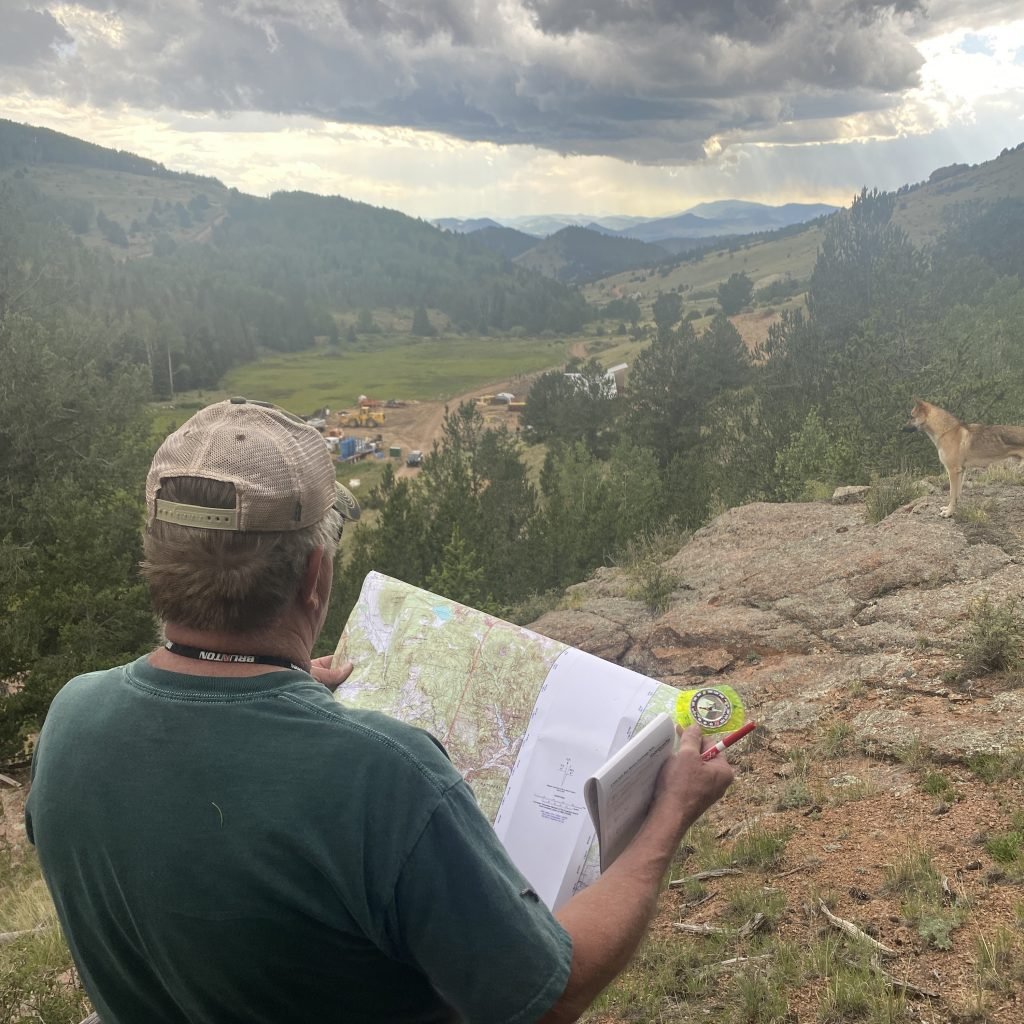

People involved in wilderness recreation are susceptible to cold injuries and the ones least aware of the early identification and treatment are the most likely to be affected. Consider the rapid change in weather, temperature and moisture, that happens daily in the large mountain ranges.

Hikes that start at low elevation may begin in warm and dry conditions that can deteriorate to near freezing rain as elevation is gained and storm fronts build with the rise of warm air. Backcountry skiers, dressed for a hard workout, can be affected if the sun goes down and the temperature drops. Proper clothing, extra layers and early recognition of cold injuries is critical to avoiding adverse outcomes.

One of the most important things to understand is that all cold injuries are preventable. From a frostbitten nose, to a profoundly hypothermic patient, we can see how someone failed to properly prepare for their adventure and how they failed to address and reverse the insidious process of cooling. Proper layering of clothes, avoiding sweating, and taking time to stop and dry out if necessary are all first line defenses against cold injuries. When traveling in the mountains it is imperative to bring a “up” and “down” layer, usually polypro long underwear and a waterproof shell, with warm beanie and gloves. Frequently assess how dry and warm you are and change your layering to avoid sweating. Avoid poor fitting shoes that can restrict blood flow or trap moisture.

When we look at cold injuries we can break them into two broad categories; systemic or peripheral. These exist on a continuum and cold injuries of the extremities are indicative of potential increase in severity to a systemic cold injury (hypothermia). Unlike many other backcountry injuries or illnesses we are able to provide definitive care if caught early enough and avoid tissue damage or a adventure-terminating injury.

All cold injuries share similar patterns of risk. People that go into the backcountry are at greater risk as are the elderly, the very young, diabetics and those that are altered or intoxicated from recreational drugs or alcohol. Age causes physiological changes (children with less surface area, elderly with less ability to sense cold) while the presence of other medical conditions, such as diabetes, can increase someone’s susceptibility to cold. Alcohol causes impairment of circulation and clouds judgement. Further, as hypothermia progresses the mental abilities of the affected will decline. The most commonly affected areas are those that are further from the warm core and the most likely to be either in damp conditions or exposed. Toes, fingertips, cheeks, the tips of the ear and the nose are the first areas showing signs. Consider these facts when obtaining a medical history from a patient.

The first and most common example of extremity cold injury is known as frostnip and this is the primary stage of the most commonly talked about extremity cold injury; frostbite. When the skin is blanched and numb, but no tissue has frozen, the exposed area has frostnip. As this injury continues without treatment the tissues will freeze, with moisture in the tissue turning into ice crystals, and the potential for permanent disability grows. We can break frostbite down into two categories as well; superficial or deep. Superficial frostbite involves the freezing of the skin layer. Skin reactions can vary from skin blanching, losing sensation and sloughing off weeks later to the formation of blisters (similar to superficial burn injury patterns). Deep frostbite involves vessels, tendons, muscles and bones being frozen. The skin takes on a mottled, bluish appearance and the area has no sensation. A good assessment is to have the patient touch his pinky to his thumb. Any loss of motor function here may be presumed to be from the cold and methods to rewarm the patient must be rapidly initiated. A patient with frostbite should be considered for immediate evacuation to avoid permanent damage.

Hypothermia, or systemic cold, is characterized in three categories. Mild or early hypothermia presents with a core body temperature from 89-96 degrees Fahrenheit. The patient will be alert and be actively shivering. A patient exhibiting shivering is still using their sugar stores to produce heat, a good sign. These patients can be warmed quickly by adding layers, building a fire, warm liquids or any combination of these.

Moderate hypothermia is a core temperature between 89.9 degrees F and 82 degrees F. The shivering process has slowed significantly and is no longer effective in producing heat and the body is shedding heat faster than can be produced. At this point the patient will begin to display a change in mentation (decreased responsiveness) and decrease shivering. Their motor skills, specifically the fine muscles, start diminishing. Blueing of the lips can be present. This is a critical time in the management of the patient. They have burned up the fuel in the tanks for the internal heater and without active rewarming techniques they will continue to lose heat and their hypothermia will become life threatening. Their ability to think clearly or perform the skills of self-rescue, such as lighting a fire, are impacted. Without immediate interventions the patient will continue to degrade into a comatose state.

The final stage of hypothermia known as severe or profound hypothermia, looks almost like death. The patient’s core temp is below 82 degrees F and they are entirely unresponsive. No shivering is present and the muscles may be rigid and fixed. At this point a pulse may be very weak and thready and difficult to locate. Pupils will be fixed. This patient requires immediate evacuation and could potentially require CPR.

In Search and Rescue, we always assume the “Three H’s” with a patient; hypovolemic (volume depleted/dehydrated), hypothermic (low body temp) and hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). Understanding this we can see that one of the best ways to defeat hypothermia is with a warm, sugary drink. Giving a patient a liter of warm water with a few tablespoons of honey dissolved in it is a easy way to introduce liquid volume, radiant heat and fuel for the muscles. In more profound cases a hypothermia wrap can be constructed with heated water bottles inside.

As a competent outdoorsman it is your responsibility to be prepared for the elements. Prevention of hypothermia is a skill that you have to be practicing every moment that you’re away from civilization. In the extreme situations of the backcountry even a small mistake like forgetting a base layer could lead to injury or death. If you’re with a group, private or as a professional guide, you must make sure everyone understands the signs and symptoms of hypothermia and the importance of frequent assessments to make sure that no one in the team is being affected.

Leave a Comment

What Nash Quinn’s Disappearance Teaches Us About Being Ready for the Backcountry

Nash Quinn vanished on a routine ride near Laramie. His story is a powerful reminder of why preparation, communication, and humility in the outdoors matter...

Recommended Gear List For Courses

Colorado is a cold weather climate most of the year and with our survival school at 9400 feet, it can get frigid at night, even…

Survival Training Near Me: Why the Best Might Be Worth the Trip

Discover why the best survival training might mean leaving the city. Explore The Survival University’s 4000+ acres and 20+ expert instructors!

Bugging In Guide Part 1: Drain Your Water Heater

Learn how to access hidden water in your home by safely draining your water heater during emergencies. A must-read for urban survival and bugging in.

Flint Knapping for Beginners: My Hilarious Failures & How to Do It Right

Flint knapping sounds easy—until you try it. Here’s my journey of frustration, flying shards, and why some people (but not me) make it look effortless.

What to Do When You Encounter a Wolf in the Wild

Wolves are neither villains nor heroes—they’re survivors. Explore their role in nature, the myths that surround them, and what we can learn from their resilience.